Aligning Economic Power with Human Values

The accelerating pace of global industrial and business development has created extraordinary opportunities—but also profound ethical challenges.

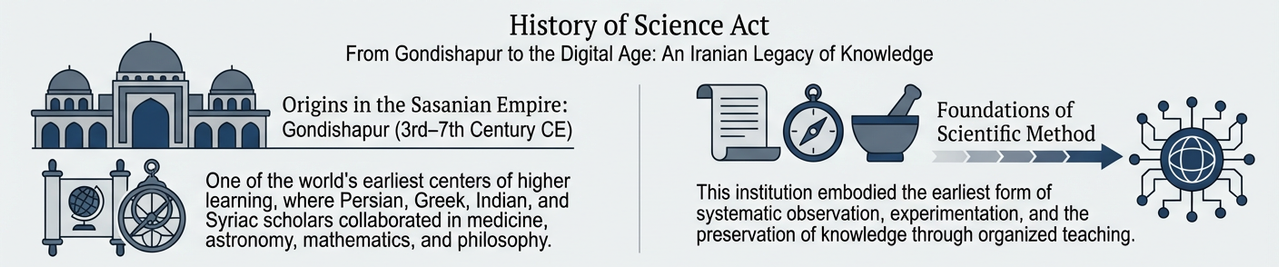

The story of Science Act begins not in the digital age, but in the ancient halls of Gondishapur, the celebrated academy of the Sasanian Empire where scholars gathered beneath the soft glow of oil lamps to heal, calculate, observe, and debate. In this institution—woven from Persian, Greek, Indian, and Syriac traditions—the earliest rhythms of scientific inquiry took organized form. Gondishapur was more than a center of learning; it was a civilizational pledge to the pursuit of knowledge, a declaration that Iran would remain a sanctuary for intellectual endeavor across the ages.

Yet the roots of this tradition reach even deeper into the soil of Iranian history. During the Achaemenid Empire, scientific thought manifested through monumental engineering, standardized systems of measurement, advanced water management, and astronomical calendars that regulated agriculture and governance. The architectural precision of Persepolis and the logistical sophistication of the Royal Road reflected a society grounded in applied mathematics, geometry, and administrative science. The Parthian (Ashkanian) Empire continued this intellectual inheritance, preserving and expanding earlier knowledge through astronomical observation, medical scholarship, and mathematical texts that later nourished Sasanian and Islamic Golden Age science.

Across the classical and medieval periods, Iran’s devotion to knowledge found expression in the works of its great masters. Avicenna, whose Canon of Medicine shaped global medical practice for centuries, formalized clinical reasoning and empirical diagnosis. Khwarizmi, father of algebra and algorithms, provided the mathematical language upon which modern science and computing rest. Nasir al‑Din al‑Tusi, working from the Maragheh Observatory, developed astronomical models that influenced the Copernican revolution. Razi, through his experimental methods and chemical classifications, laid foundations for modern chemistry and clinical medicine. Farabi and Mulla Sadra explored the architecture of thought, logic, and epistemology, shaping the intellectual frameworks through which scientific reasoning operates. Giyath al‑Din Jamshid Kashani advanced mathematics with extraordinary precision, calculating π to unprecedented accuracy and formalizing decimal fractions centuries before their widespread adoption. Scholars such as Biruni, Omar Khayyam, and the Banu Musa further enriched astronomy, geometry, mechanics, and comparative scientific methodology.

These achievements were not isolated moments of brilliance; they were the unfolding of a continuous Iranian tradition—one that regarded knowledge as both a duty and a form of beauty. Long before the modern English word science emerged from Latin scientia, Iranian scholars were already practicing the disciplined acts that define scientific method: observation, experimentation, classification, calculation, and philosophical inquiry. In this sense, the name Science Act resonates deeply with Iranian intellectual history. It reflects the understanding that science is not merely a collection of facts but an act—a deliberate, rigorous, and humane pursuit of truth.

In the modern era, as Iran’s universities, research institutes, and scientific communities expanded, a new need emerged: a journal capable of honoring this profound heritage while engaging with the global scientific landscape. Responding to this need, Science Act was founded in 2024 as an Iranian, open‑access, multidisciplinary journal committed to rigorous peer review, editorial transparency, and equitable access to knowledge. Its mission is to carry forward the ancient flame of inquiry into the digital century, connecting the wisdom of Gondishapur and the classical scholars with the frontiers of contemporary research.

Today, Science Act stands as a bridge between Iran’s scientific past and the global scientific future. It embodies a lineage that stretches from Achaemenid engineers and Parthian astronomers to Sasanian physicians, medieval polymaths, and modern Iranian researchers. Above all, it affirms a timeless belief: that science, at its heart, is an act of humanity—an enduring expression of curiosity, responsibility, and the shared pursuit of understanding.

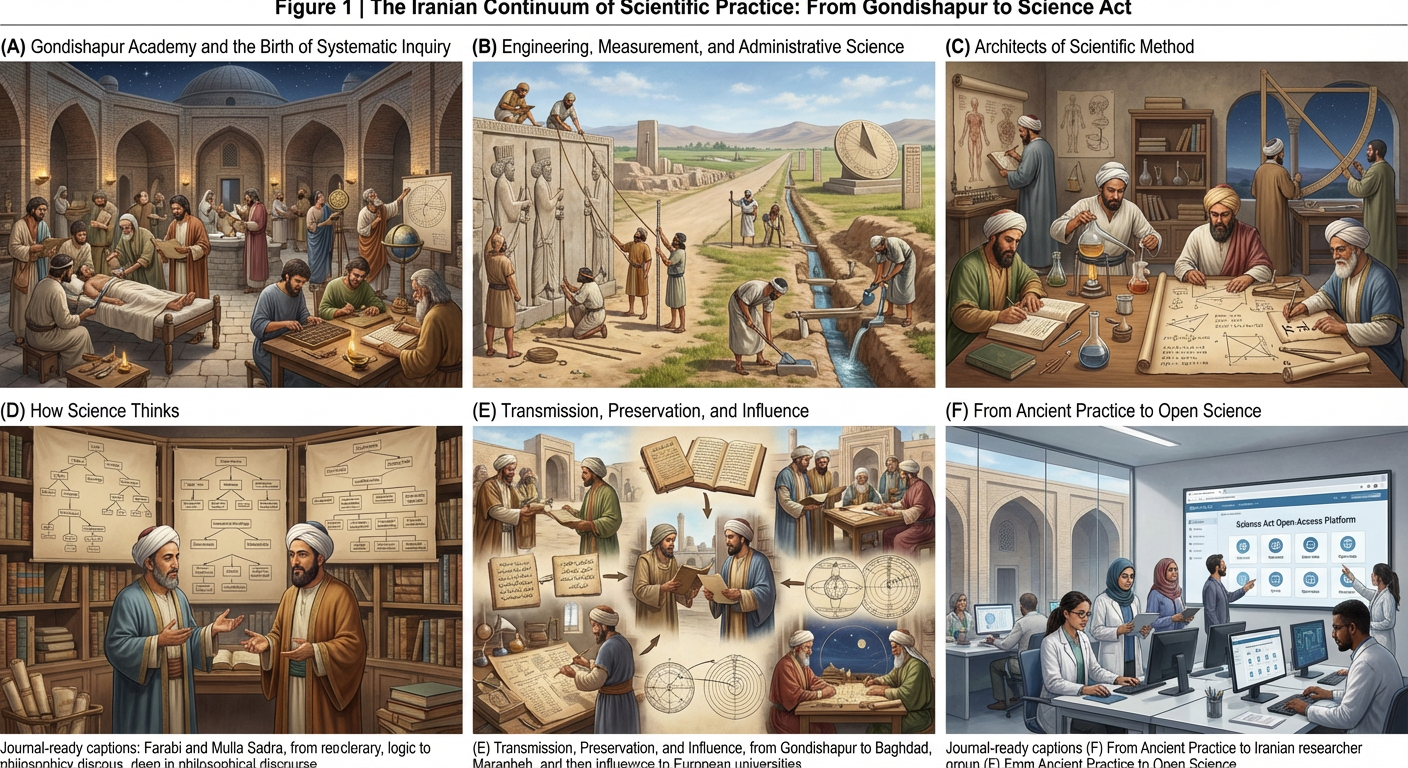

Figure 1 | The Iranian Continuum of Scientific Practice: From Gondishapur to Science Act.

(A) Gondishapur Academy of the Sasanian Empire (3rd–7th century CE), illustrating one of the world’s earliest institutionalized centers of higher learning, where Persian, Greek, Indian, and Syriac scholars practiced systematic observation, experimentation, and organized teaching in medicine, astronomy, mathematics, and philosophy.

(B) Applied scientific knowledge during the Achaemenid and Parthian periods, manifested through monumental engineering, standardized measurement systems, advanced water management, astronomical calendrics, and administrative logistics, exemplified by Persepolis and the Royal Road.

(C) The classical Iranian polymaths—Avicenna, Razi, Khwarizmi, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, and Giyath al-Din Jamshid Kashani—who formalized empirical medicine, controlled experimentation, algebra, astronomical modeling, and mathematical precision, establishing foundational methodologies of modern science.

(D) Epistemological frameworks developed by thinkers such as Farabi and Mulla Sadra, depicting the philosophical architecture of scientific reasoning, logic, causality, and knowledge validation that underpins rigorous inquiry.

(E) The transmission and preservation of Iranian scientific knowledge across civilizations, from Gondishapur to Baghdad, Maragheh, and Europe, through translation movements and scholarly exchange that influenced the global development of science.

(F) Science Act (founded 2024) as a contemporary, open-access, multidisciplinary journal representing the modern continuation of Iran’s long-standing scientific tradition—bridging ancient scholarly practice with global, transparent, and reproducible research in the digital era.

The accelerating pace of global industrial and business development has created extraordinary opportunities—but also profound ethical challenges.

A healthy climate and protected environment are essential for human survival, biodiversity, and long‑term economic stability.

Journal Scope

Science Act is a multidisciplinary journal that focuses on advancing scientific knowledge across various fields. It publishes original research, reviews, and articles that explore diverse areas of science, including biology, chemistry, physics, engineering, and environmental sciences. The journal employs a rigorous peer-review process, ensuring the quality and credibility of the content it publishes. This process fosters the validation of research findings and encourages scholarly dialogue. By bridging the gap between different scientific disciplines, Science Act serves as a platform for collaboration, innovation, and the dissemination of groundbreaking discoveries that address global challenges. ISSN: 3115-7262

Funding Statement

All accepted articles are eligible for full publication funding under the Science Act Flagship Journal Program. Funding support is guaranteed for manuscripts published before 2027, ensuring that authors face no article processing charges and can benefit from broad dissemination of their work. This initiative reflects our commitment to supporting high‑quality scientific research and fostering global accessibility to new knowledge. For more information please check Funding programs

Cookies are used by this site.

“Authors retain copyright of their work and grant Journal Science Act a non-exclusive license to publish the article under the CC BY 4.0 agreement.”

Attribution 4.0 International CC BY 4.0 Deed: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0

.png)